Surrounded by framed photos of his sons Nox and Leo Martin and a series of him falling off at the Head of the Lake during some Kentucky CCI5*-L run, Boyd Martin gazes out his back window and says, “I’m a pretty confident person, but I would say deep down, I don’t think I’m that good, technically.”

I’m in Cochranville, Pennsylvania, at Windurra USA, to speak to Boyd about a year of accomplishments that led us to select him as the Chronicle’s Eventing Person of the Year and his partner On Cue the Horse of the Year.

But beyond his humorous, always quotable Aussie exterior, he’s intensely driven by the fact that he can—and will—be better. Though grand, 2021 isn’t Boyd Martin’s final destination.

“I look at Steffen Peters ride dressage, and I think I’d be embarrassed if I rode in the ring at the same time as him,” Boyd says. “Or watch McLain [Ward] show jump a horse; I think his understanding of training and jumping a horse is in another stratosphere to me. I enjoy that thought that I’ve obviously got a lot more to learn and a lot more to get better.

“I feel like I’ve got that unhealthy obsessiveness and hunger to win,” he adds. “Half of the really, really good people I’ve met [are] half nuts. And I think you’ve got to understand that to be really, really good, you’ve got to have a little bit of a screw loose. To make sure that you still can switch that off a little bit, and be a good parent, and not be so competitive that you lose all your friends—there is a very [delicate] balancing act. But I think to be very, very good you have to understand that you have to sacrifice a lot, and you lose a big part of the elements of your life. I’m comfortable with that. I just don’t want to be normal.”

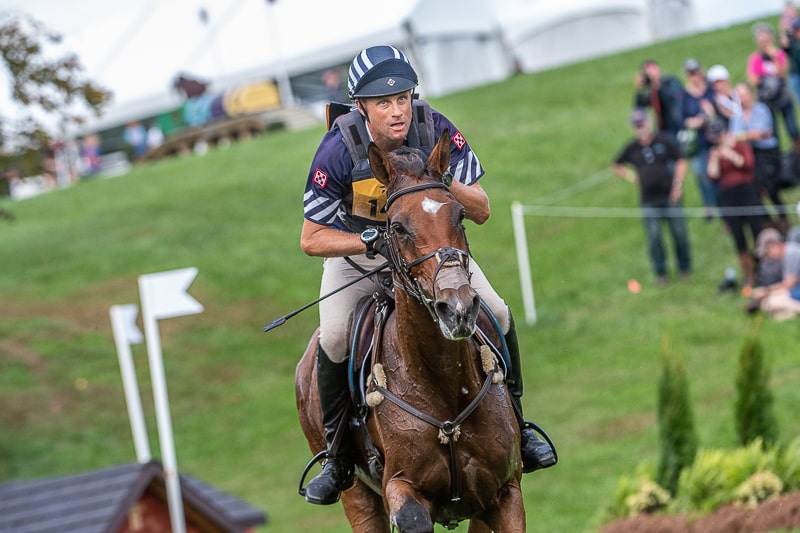

Boyd Martin and On Cue were nearly unbeatable in 2021. AK Dragoo Photography Photo

Igniting The Fire

Boyd can’t pinpoint exactly when he started sprinting away from normalcy.

With a cup of tea in hand, he says, “From a very young age, I had this belief that I was one of the best.”

Sports played an ever-present role in his childhood as the son of two Olympians. (His mother, Toy Dorgan, was a speed skater, and his father, Ross Martin, was a Nordic skier.) After graduating high school, he followed the equestrian calling to a working student position and a bunk house. But like many up-and-comers, he remembers years of waiting to be noticed.

“To be honest, when I was riding for Australia, there were times and moments where I did think it was unachievable,” he says. “Just because when you’re younger, and you’re starting out, the riders at the top just seem like they’re just another dimension to you with the way they compete, the horses they have, the business set up they have, the grooms, the staff, the farms, the trucks, the lorries. You’re a one-horse person that’s all eggs-in-one-basket [with] some horse you bought off the racetrack for a thousand bucks. You have this wonder of, ‘How could I possibly compete?’ ”

Then, in 2003 he won the Adelaide CCI5* (Australia) with True Blue Toozac.

“It wasn’t until I won Adelaide five-star that everyone seemed to start getting behind me a little,” he says. “It was a little bit of a long run until then, but as soon as you win a big event like that, all of a sudden, people around you start seeing what you’ve been believing within yourself all that time.”

At 23, he’d earned the victory that would kick off his career.

“I’d done a couple of five-stars before, but it was the first time that I really went for it,” he said. “I learned at that event that to win it you have to really go for it. You can’t take an option; you’ve got to go for broke. Honestly, at that age and at that time, I thought, ‘All right, this is going to happen often and easily.’ ”

Four years later, Boyd moved to America. He started riding on U.S. teams in 2009, and he learned how naïve he’d been at 23.

“I worked hard and pushed hard, and years went by, and decades went by where I’d come really, really close to repeating that result but never quite pulled it off,” he says. “There was always this self-belief that I was just as good as the other guys, but there were just moments in time where things just didn’t fall my way. Shamwari [4] was leading Luhmühlen [Germany] and unfortunately didn’t trot up after the cross-country. ‘Thomas’ [Tsetserleg TSF] came second by a close call in Kentucky. And Otis [Barbotiere] finished third at Rolex.

“On Cue was in there for a bit of a fight this year,” he continues. “You start wondering if it’s ever going to happen.”

Boyd Martin made history at the Maryland 5 Star at Fair Hill, riding On Cue to become the first American to win at the level in 13 years. Kimberly Loushin Photo

Good Questioning

Boyd’s clinic-teaching schedule spans the coasts, taking him away from Pennsylvania much of the winter. But on a quiet off week, he strips the clinician microphone and zips up his shined tall boots to travel down the road; he’s still heading to a clinic but not his own. Instead, he’s riding with Olympic show jumping gold medalist Joe Fargis.

“There’s this desperation of hunger for just continuous improvement,” Boyd says. “I still truly think that I can get a lot better. I don’t think I’ve reached my pinnacle in my ability. I’m 42 years old; I want to keep doing this until I can’t walk. The next 10-year window of my life is so critical in [my] legacy and in what I want to achieve. Part of it is getting the very best horses I can get my hands on, and Part B is coming up with a system of riding, a system of training and competing, that’s better than I’ve ever been. I think to have that mentality and that mindset to get better.”

Boyd comes armed with a slew of mentors, from former U.S. performance director Erik Duvander to show jumping Olympic gold medalist Peter Wylde, from teammate Phillip Dutton to wife and Grand Prix dressage rider Silva Martin.

“What gives him that edge is that he’s questioning all the time—and not in a bad way, in a good way,” says Wylde. “He’s not ‘doubting’ questioning. He’s asking: ‘Is this the right way to do it? Can I do it better?’ and getting that opinion. He’s open to hear what another professional will say to him. That sort of instinct to strive for perfection is what makes a really top athlete. Boyd, he doesn’t rest on any result that he’s had.”

Duvander says this pursuit of excellence is constant. “He never sees himself as the full rider yet,” he says.

Before the sun rises, Duvander points out, Boyd’s in the gym stretching and accommodating his previous injuries so that his horses receive the best he can offer.

“He’s already done an hour-and-a-half’s work on himself and his body to be in best shape before he even climbs on his first horse,” Duvander says. “This is a dedication [that’s] beyond most. This is where LeBron [James] and all these top world class athletes, they operate in that level. And that’s what Boyd does.”

A win at the USEA American Eventing Championships(Ky.) put On Cue and Boyd Martin on the path to a stellar fall season. Lindsay Berreth Photo

Preparing To Show The World

It’s flurrying at Windurra, and Cue gently licks my icicle fingertips as assistant groom Jessica Gehman grooms the 15-year-old Anglo-European mare (Cabri D’Elle—On High, Primitive Rising). Gehman confides that after Chattahoochee Hills Horse Trials (Georgia) in 2020, she felt the next year would be On Cue’s breakout year.

On paper, it’s an odd memory to use as the memory. Cue finished 11th in the advanced, but the deluge of Georgia rain prevented cross-country from running.

“She just jumped so well in the mucky footing,” Gehman explains. “Like it had poured with rain. It was torrential downpours. Cross-country course is totally ruined. They couldn’t run anything. And she just jumped so well in this terrible arena footing that they couldn’t do anything about, and I just knew, this is the horse of a lifetime.

“It just really showed who she was as a horse and the big heart that she has and the desire to just want to please her rider,” she adds. “They’re such a good team. I was like, ‘This girl, she has it all. She has the look, the feel, the attitude and the grit to get it done no matter what circumstance.’ ”

Boyd had tried to buy the mare in 2014 when Sinead Halpin was riding her at the preliminary level, but it didn’t work out, and owners Christine, Thomas and Tommie Turner sent the horse to Michael Pollard. When Pollard stopped competing, Christine sent Tsetserleg to Boyd—and then came On Cue.

“[She said], ‘I’ve got this mare On Cue that’s just been in the field [in Texas] for two years doing nothing; I want to send her to you to sell,” Boyd says. “And I mean, I couldn’t believe that it was the same horse.”

The mare needed training, fitness and confidence as they started their first competitions in 2017. As Boyd built those basics, he said they had some “up and down” results, but they were quickly winning at preliminary and intermediate.

“She missed out [on] a lot of the fundamental years of education and building strength,” Duvander says. “Over the years I’ve known her, she’s always had the right attitude about everything, but she never had the full amount of strength to carry off the job and in as good a way as she should have—and that’s not the horse’s fault. It’s just that it was being a bit wasted for a while before it came to Boyd.”

Boyd sees every horse in his barn as a five-star horse, and that confidence allows personalities like “Cue” to blossom.

“One of the many great attributes of Boyd is when he’s got a horse, he 100 percent believes in the horse,” says Dutton. “To a degree I think sometimes he puts a bit of belief in horses that he probably shouldn’t. Right from the get-go, he’s just loved this mare. She’s obviously been in a few other hands before Boyd got her. That belief in her, it certainly has fed off into [her], and she just believes in Boyd.”

Duvander said Boyd sees the good in the horses. “Horses love him. They step up for him. I’ve seen horses do phenomenal things with him that they wouldn’t have done with anyone else,” he says.

Cue was booted off of the USEF Pre-Elite Training list in November of 2020 after pulling two rails at the Tryon International Three-Day Event (North Carolina). But Christine didn’t harbor any concerns: “I told Boyd, ‘You know, when one of my horses gets kicked off, it kind of makes me feel good because I know you’re going show the world.’”

Boyd Martin’s belief in On Cue paid off with his biggest win to date at the Maryland 5 Star at Fair Hill. Kimberly Loushin Photo

A Record-Book Year

While watching Boyd and Cue tackle the cross-country at the USEA American Eventing Championships (Kentucky), Wylde noticed a change in the mare’s expression. She’d already claimed fourth—the highest U.S. finish—in her five-star debut at the Land Rover Kentucky CCI5*-L. From there she made it onto Boyd’s Olympic roster as one of his three mounts poised for Tokyo. As the direct reserve horse behind Thomas, Cue received team training during the pre-Olympic quarantine in Aachen, Germany.

To Wylde, that August run in Lexington, Kentucky, to win the $60,000 Adequan USEA American Eventing Championships Advanced Final marked a turning point.

“When you watched her galloping across country, you could see the look in her eye was different from even the year before,” says Wylde. “Her ears were forward, and her expression was super positive. Whereas before, like a year earlier, she was doing it, but you could tell that there was an anxious look on her face.

“I believe that in her body, she felt better,” he adds. “She felt stronger, fitter, and it took time. And then she started to realize, ‘Ah, I can do this. It’s not so hard.’ And you can see it—you could see it in her expression as she was doing her job. Because that mare, she has the biggest heart. She wants to do it. But when Boyd started with her, I don’t think she believed she could do it. He gave her that confidence to believe in herself.”

In August, Boyd rode Thomas on the U.S. team at the Tokyo Olympics, but the squad’s sixth place finish there wasn’t what he’d dreamt of. On the long flight home, he tried to put Tokyo behind him and move onto his next focus: riding Cue at the inaugural Maryland 5 Star at Fair Hill.

“The one thing I’ve learned after being in this game for so long is you can’t mope around too long,” says Boyd. “You can’t change the past. It’s a moment in time you can’t go back on. And true champions bounce back. [For] months and months I’ve been dialed in before the Olympics for On Cue at Maryland 5 Star, so that was with or without the Olympics, or whatever the scenario situation is. I was on a mission to give a top performance at that Maryland five-star.”

And Christine likewise was on a mission.

“They said, ‘Will you leave Cue over there [to compete in CHIO4*-S Aachen in Germany after the Olympics]?’ ” she remembers. “I said, ‘No, I want her to win the Maryland 5 Star.’ ”

On a cloudy October day in Maryland, as the starter counted down in the start box, Boyd made a deal with himself to see it through.

“It’s easy to talk big game in the months before the five-stars of what you’re going to do,” says Boyd. “But the last 10 minutes when it’s pouring with rain, all the other horses are coming home tired, there are riders falling over at the tough jump, it’s very easy to quickly talk yourself into just getting around. What I’ve discovered is, the final minutes before you start, you have to take a deep breath and make a deal with yourself that you want to win.”

Cue called Boyd’s raise with a clear cross-country run. On the final day, she rattled a few rails in their cups but still produced a clear round to at least maintain their overnight third place. Boyd was walking her quietly around the warm-up ring awaiting the results of the last two riders when Duvander came sprinting toward him with the news.

“Just that look on his face when I came over and saw him and said he’d won,” Duvander remembers. “Those moments, you get them every now and then in sport, but it just sort of blows me away.”

Thinking back on that day, Boyd doesn’t romanticize details. He doesn’t talk about his son Leo fittingly wearing a Superman sweater. He doesn’t point out the few—apparently extremely rare—tears he wiped away. For the chatty personality Boyd’s trademarked, he’s oddly subdued.

His recollections come with a tone of relief and an awareness of the bigger picture. He still harbors more dreams and sees more work to create the legacy he wants. But regardless, Cue gave him a notch in his record book that brought him one step closer to fulfilling that self-belief.

“To have a five-star win—I’ve truly been chasing this five-star win since I’ve been 23 years old,” he says. “There hasn’t been a year gone by in the last 18 years. Every year I felt like I had a horse with a chance of doing it. It was a huge sigh of relief that finally I pulled it off in Maryland on Cue. And I look back on that, it’s a special moment in my life and time where you feel like all the hard work, the injuries and the setbacks were actually all worth it.”